- Home

- Eternity Martis

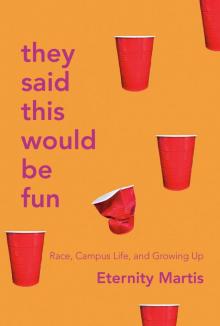

They Said This Would Be Fun

They Said This Would Be Fun Read online

PRAISE FOR

They Said This Would Be Fun

“I’m angry to hear that Canadian universities are still ignoring and isolating young racialized women, decades after my own experiences there. But I’m very glad that Eternity’s brave, honest, and funny book will be there for students of the future—as well as for institutions whose leaders have the courage and decency to change.”

—Denise Balkissoon, Executive Editor, Chatelaine

“With fierce intelligence and flashes of humour, Eternity Martis exposes racism and sexism on contemporary university campuses through her personal story of coming of age as a young Black woman at a predominantly white school. A deeply felt memoir about resistance, resilience, and the life-saving power of finding your own voice.”

—Rachel Giese, author of Boys: What It Means to Become a Man, winner of the Shaughnessy Cohen Prize for Political Writing

“In her debut memoir, They Said This Would Be Fun, Eternity Martis maps out the very real ways that structural violence permeates the lives of young Black women in predominantly white schools in Canada. Her writing is both candid and alluring and perfectly delineates how race, gender, and sexuality are all intertwined in everyday events of university life. This book is an urgent read for all educators and education administrators, those who are considering university and college life in Canada, alongside young Black and racialized women who are looking to be seen.”

—Huda Hassan, writer and researcher

“Though They Said This Would Be Fun is Eternity Martis’s debut, she is an authority on the pervasive nature of racism on North American university campuses—an oft-overlooked issue kept hush among so-called polite Canadians. They Said This Would Be Fun is not an easy read, nor is it always comfortable. But it is an essential book for allies—an exhaustive look at the discrimination Black women face in a country too often described as a haven of multiculturalism.”

—Erica Lenti, Senior Editor, Xtra

“Too many stories about the experience of racism on Canadian campuses remain buried, because of fear of reprisal or retaliation. With this spellbinding and important memoir, Eternity Martis offers us a clear-eyed, eloquent, and no holds-barred portrayal of what it’s like to be a young Black woman studying in the ‘ivory tower.’ Required reading for all those who are preparing to head to a Canadian university—and to those who head them up. I plan to buy it in bulk to hand out at my school. Unwaveringly unapologetic, richly written, and powerfully conveyed, Martis offers us the book that scholars, students, and university administrators have been waiting for—an unflinching look at racism on Canadian campuses. Following in the footsteps of writers like Roxane Gay and Scaachi Koul, but steadfastly providing her own distinctive voice, Martis’s book is at times shocking, powerful, surprisingly funny, and most of all provides a seamless link between theoretical approaches to race and how it plays out in practice.”

—Minelle Mahtani, Associate Professor, Department of Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice, and Senior Advisor to the Provost on Racialized Faculty, University of British Columbia

“University is a time of major personal growth and excitement but also systemic, baked-in discrimination and inequity. This book is for anyone who is still making sense of it all but especially for those who need communion with a beautifully-written account of what it’s like to finally find your people.”

—Hannah Sung, journalist

Copyright © 2020 by Eternity Martis

Hardcover edition published 2020

McClelland & Stewart and colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Limited.

All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrieval system, without the prior written consent of the publisher—or, in case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency—is an infringement of the copyright law.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication data is available upon request.

ISBN: 978-0-7710-6218-6

ebook ISBN: 978-0-7710-6219-3

Excerpt from bell hooks, Black Looks: Race and Representation (Toronto: Between the Lines, 1992) reprinted with permission from Between the Lines.

Excerpt from “The Uses of Anger” from Sister Outsider, Crossing Press/Penguin Random House, Copyright © 1984, 2007 by Audre Lorde.

Excerpt from for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf by Ntozake Shange. Copyright © 1975, 1976, 1977, 2010 by Ntozake Shange. Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a division of Simon & Schuster, Inc. All rights reserved.

Cover art and book design by Kelly Hill

McClelland & Stewart,

a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited,

a Penguin Random House Company

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

v5.4

a

For M and D, for everything.

“If you are silent about your pain, they’ll kill you and say you enjoyed it.”

—ZORA NEALE HURSTON

contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

All I Wanted Was to Be Wonder Woman

Token

Go Back to Your Country

Visible Bruises

Party Gastritis

Anthony, My Italian Greek Tragedy

Relationshit

At All Costs

The End of the Rainbow

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

introduction

As I launched out the window of an inflatable bouncy castle, into the warm autumn air and then the mud below, the only thought undiluted by copious amounts of alcohol was: This is what freedom feels like.

It was Saturday, the last night of Orientation Week, and hundreds of first-years were coming together to celebrate on University College Hill, a giant grassy quad on campus. Western University was known for having the most epic frosh week in Canada, especially on the last night, when a B-list Canadian band always played. This year, it was Down With Webster. Sex with Sue, the infamous old lady who we watched after-hours on TV while our parents slept, would show us how to put on condoms, and loud music would play all night alongside carnival games, corporate sponsors and their free grub, and bouncy castles.

A week ago, I had been sobbing in the basement of the house where I grew up, clutching my high school boyfriend’s tear- and snot-stained shirt and cursing myself for thinking I could handle moving away from home. I cried the whole way to London, past the small cities I had never heard of and the luscious Green Belt. I cried as I walked up to my new room in Medway-Sydenham Hall and looked at the small space, crammed with two twin beds and two desks, that my best friend Taz and I would be sharing. I cried as I unpacked boxes, as I put my mattress protector on, as I wiped down empty drawers, as I unloaded my underwear from the vacuum-sealed bag and folded them neatly. I cried as I closed the drawer. I cried when I realized there were no other brown-skinned girls on our floor besides us. I cried so much that my floormates and their parents were calling me “the crying girl.”

The welcome package had given us tips on how to pack, but it didn’t specify how much we needed to bring. My family didn’t know either—I was the first and only one to go to a Canadian university—so I brought every bra I owned, every spare sock,

pair of shoes, and picture frame from my bedroom. It took twice as many sophs, the volunteer students who help first-years adjust to student life, to haul my stuff up to the third floor and make it fit into the shared fifteen-by-twelve-foot space. At one point, they lost the bag full of my pants and I was inconsolable, thinking that I’d have to walk around pantless because nobody would sell fashionable bottoms in a place nicknamed “Forest City.”

When I had told people back home that I was going to Western in the fall, they had similar comments: It’s the best school. It’s a party school. It’s a white school—why would you go there? Their eyes widened and they’d lean in, whispering as if they were afraid of someone hearing, and say that London was notoriously white, Christian, and conservative. They told me cautionary tales of family and friends transferring out of the school after years of microaggressions and racial harassment on and off campus. “Don’t worry though,” they’d say with a smile. “You’ll have fun.”

It had never occurred to me that other cities in Ontario wouldn’t be as welcoming as the one where I’d grown up. In Toronto, there was always a mix of various ethnicities—Chinese, German, Filipino, Trinidadian, Somali, Indian, Pakistani, Sri Lankan, Jamaican, Guyanese. You can find numerous types of cuisine, schools, and places of worship on any given block. All around, people look like you and look unlike you and it’s nothing to fuss about.

But listening to people’s concerns, it was like I had chosen the Alabama of Canada to spend the next few years of my life in. It wasn’t that my hometown was exempt from racism—I knew which department stores would send their white employees following after me like a criminal, and I understood the intentions of the police when my peers would get stopped on their way home from playing basketball. But I was sheltered; I hadn’t gotten a complete picture of what it meant to be a Black girl at home before I left to become a Black woman in London. I wondered if I could form my own identity surrounded by white kids wearing Hunter boots and Canada Goose jackets. I worried I could be alienated for being “too Black.” I was even more worried about losing myself and being called “too white” when I got back home.

But people in London were friendly. They smiled as you passed by. Strangers said good morning. Everyone talked to me—the women in line at the grocery store; the people sitting next to me at a restaurant; the students also waiting an unacceptably long time for the bus. But many of our conversations ended up diverting into race. We don’t get a lot of Black people here. London has become very progressive in the last few years. My God, Black people are just so funny. Where are you from? No, no no, like where did you originally come from? Ethiopia? Kenya? Zimbabwe? Africa? As the months and years went on, these seemingly innocuous comments became more ignorant, and at times, malicious.

From the ages of eighteen to twenty-two, I learned more about what someone like me brought out in other people than about who I was. I didn’t even get a chance to know myself before I had to fight for myself.

In the four years I spent in London, Ontario, for my undergraduate degree, I was called Ebony, Dark Chocolate, Shaniqua, Ma, and Boo. I encountered Blackface on Halloween and was told to go back to my country on several occasions. I was humiliated by guys shouting, “Look at that black ass!” as I walked down a busy street. I was an ethnic conquest for curious white men, and the token Black friend for white women. I was called a Black bitch and a nigger. I was asked by white friends desperately trying to rap every song off Yeezus if it was okay to use nigga around me. I was verbally assaulted and came close to being physically attacked by angry men. I came face-to-face with a white supremacist. I was asked if I spoke English and whether I was adjusting to Canadian winters. When I told people I was born in Canada, they’d impatiently badger me with, “But where are you really from?”

These encounters were about how I was perceived, not who I actually was—someone always in between worlds: a Canadian-born girl with two immigrant parents; a multiracial woman with Black features in a family of brown people; a daughter raised by a working-class mother and middle-class grandparents; the only baby born out of wedlock in a family all conceived after marriage; an only child with at least seven half-siblings; an astrology-lover born right on the cusp of Taurus and Gemini.

I have lived in the squishy middle all my life, at the margins of binaries—an experience that has made me as independent as I am lonely.

I felt trapped by these categories, whose walls felt so high that I might never get out. I wondered what kind of person I was outside those confines, and university seemed like a good place to start solidifying the pieces of myself that I felt I couldn’t explore back home.

A few things did solidify about my identity while I was there: I was Black, I was a woman, and I was out of place. I didn’t identify as Black until I got to London. This is common among people who come to Canada from countries with diverse ethnic communities, or who grew up in a mixed family where identity wasn’t discussed. I wasn’t ignorant to my own appearance; I definitely didn’t pass as white, and there was no way I looked brown. At home, being a racial minority meant you belonged somewhere. In London, it was a marker of exclusion and difference, and you were squeezed into a category—Black, White, Asian, Brown—that became a way to navigate and survive the environment.

My maternal grandparents, who raised me for the first half of my life, faced racism themselves when they arrived in Toronto from Karachi, Pakistan, in the early 1970s. But they didn’t know what to make of my claims of anti-Black racism. We never spoke about my father, a Jamaican man, who was absent, or what his ethnicity meant for my own identity. My family was shocked to hear me call myself Black, and even more shocked at the stories I told, despite police-reported hate crimes across the country soaring the year before I went to Western, and London having one of the highest rates of all Ontario metropolises. It was 2010, and we were only starting to get to a place where advocacy journalism and personal essays extensively covered these problems. Modern Black writers like Ta-Nehisi Coates, Roxane Gay, Kiese Laymon, Morgan Jerkins, Reni Eddo-Lodge, and Ijeoma Oluo had yet to get the recognition they deserved—or even to write their stories. I had few examples to prove racism was a common occurrence and not an isolated experience.

My family thought that perhaps I was exaggerating. That I had developed a new, somewhat militant eye for race issues. Plus, I was so angry these days—maybe my irritability, they gently offered, was causing me to misunderstand people’s intentions.

Of course I was angry. Instead of focusing on classes and adjusting to my new life as a student, everything had become about the skin I was in. I became a survivor of both inter-partner violence and sexual assault, and had to fight stereotypes about not being the perfect victim. Anger and fear were so etched in my body that I often felt I had no control over myself. Why could people take their anger out on me, but mine was irrational?

I internalized people’s doubts about my experiences. I grew stressed, anxious, and depressed, coping with food, alcohol, and partying. In public, I devised exit plans in case I was harassed. Everywhere I went, even in my own home, I felt a constant, electrifying pressure in the air, as if violence could erupt at any moment.

I kept a record of all the instances where I had been the target of discrimination, harassment, and microaggressions, scribbling them down on pieces of paper—notes to myself, a way to make sense of what was happening. At school, I naturally gravitated towards students of colour who were having similar experiences. Some couldn’t make it, even with our support system, and they dropped out or transferred schools. I decided to stay, weighing up the discomforts of starting over someplace new and the discomfort I was already familiar with. I accepted the emotional cost of this decision.

The year after I graduated from Western, I wrote a reported personal essay for Vice Canada, titled “London, Ontario, Was a Racist Asshole to Me.” I interviewed current students, city councillors and locals. The essay sparked heated discussions in h

omes, in city council, and in universities, and is still a point of reference for media when discussing race-related issues such as carding, the illegal police procedure of randomly stopping people of colour and collecting information.

I received hundreds of messages from people who read the article. Londoners promised to be better allies. People who had witnessed the racial harassment of friends asked for advice on how to intervene. Older folks recalled their experiences from decades ago, saying things hadn’t changed. People of colour of all ages and backgrounds shared their own stories.

Londoners confessed secrets about the tricks their bosses used to keep Black people out of their establishments. Women and LGBTQ2S+ people told me about their own horrible experiences, from verbal slurs to physical assault, especially in nightclubs. Former residents of London told me they’d left because the racism was so bad. Current inhabitants told me that they were afraid for their lives.

Most of all, students attending other post-secondary schools in Canada shared their experiences and concerns, many of which mirrored my own. And high school students messaged me, worried about which colleges and universities were racially tolerant. In the years following the article’s publication, I’ve met students of colour around the world who’ve told me stories of the racism and isolation they experienced while attending university in the U.K., Australia, and the U.S.

To be clear, this isn’t just a Western University problem. Here in Canada, we have nearly one hundred universities and even more colleges, and yet there’s no evidence that we collect race-based data on students, so it’s impossible to know how many are visible minorities and what their needs and challenges are. There is also no unified, formal policy across schools on dealing with racism. Many students don’t report incidents because they fear they won’t be believed.

They Said This Would Be Fun

They Said This Would Be Fun